GREENWOOD, Miss. (AP) – Betty Sibley had just gotten out of the shower and was about to lay down to relax when she realised something was amiss.

Her arms were breaking out in hives, and her throat was swelling shut. Both were indicators that she was having a possibly fatal allergic response.

An EpiPen was put into her leg by a first responder, and an ambulance rushed her to Greenwood Leflore Hospital, about 5 miles away, where emergency room staff took control, delivering steroid doses.

“I would have died if it had not been for this hospital,” she said.

Now, the hospital she went to in an emergency is struggling to stay open.

The regional hospital’s cash reserves have dropped in the last year, and patient traffic has reduced. Many of those who do come are uninsured, which means that the hospital is unlikely to be reimbursed for their care unless they pay out-of-pocket or seek other forms of financial assistance. Greenwood Leflore is currently paying more than $100,000 per month for the Medicare loan that aided the hospital during the epidemic.

Hospital administrators have attempted to slow the crisis by laying off employees and reducing services. Pay incentives that had helped keep the hospital staffed were eliminated by administrators. Greenwood Leflore’s labour and delivery unit was closed this fall due to a lack of staff. The hospital’s pulmonology clinic will close on November 30 due to low patient volume and revenue.

Greenwood state Sen. David Jordan is concerned about residents who will die “necessarily” if the hospital closes.

“The only hospital we’ve got is on its deathbed,” he said.

Greenwood Leflore’s financial difficulties are the latest setback in a predominantly Black Mississippi Delta community that has been hard hit over the last two decades by the closure of major manufacturers, a teacher shortage in its public schools, and steep population loss — there aren’t enough newcomers to replace those who have left or died.

Generations of people have breathed their first and final breaths at Greenwood Leflore Hospital, despite the town’s difficulties. It is also an important economic driver. The medical hospital is one of the main employers in a community where many families struggle to put food on the table.

The hospital’s condition deteriorated during a few weeks this autumn, with interim CEO Gary Marchand admitting in a staff message that it may collapse by the end of the year. On November 4, discussions with a larger Jackson hospital that local leaders believed would take over Greenwood Leflore fell down.

Marchand thinks that the hospital will require $5 million to $10 million in order to remain operating until next summer. While some banks are eager to help, he says municipal and county leaders will have to help the hospital secure the resources.

“We will not make it into 2023 without funding,” he said.

Leflore County Supervisor Board President Robert Collins stated that the county’s finances are already stretched, but that the county can most likely contribute $3.5 million to Greenwood Leflore. He warned that the county will not be able to keep the institution running indefinitely.

“We can’t generate that money in the county,” he said. “We don’t have that kind of tax base.”

Greenwood City Council President Ronnie Stevenson acknowledged that the city might need to provide aid as well.

He’s adamant that he doesn’t see closing the hospital as an option, but he is blunt that he doesn’t want to “keep throwing water on a sinking ship.” At a minimum, he said, the hospital, which lost almost $2 million last month, has to start breaking even.

A more comprehensive fix could arrive in the spring, when Marchand hopes the Legislature will approve a statewide plan to push more Medicaid funding to hospitals.

“We have to find a governmental solution, if we’re going to be viable in the long-term,” Marchand said.

The community may have to wait months for an answer with the hospital’s fate hanging in the balance.

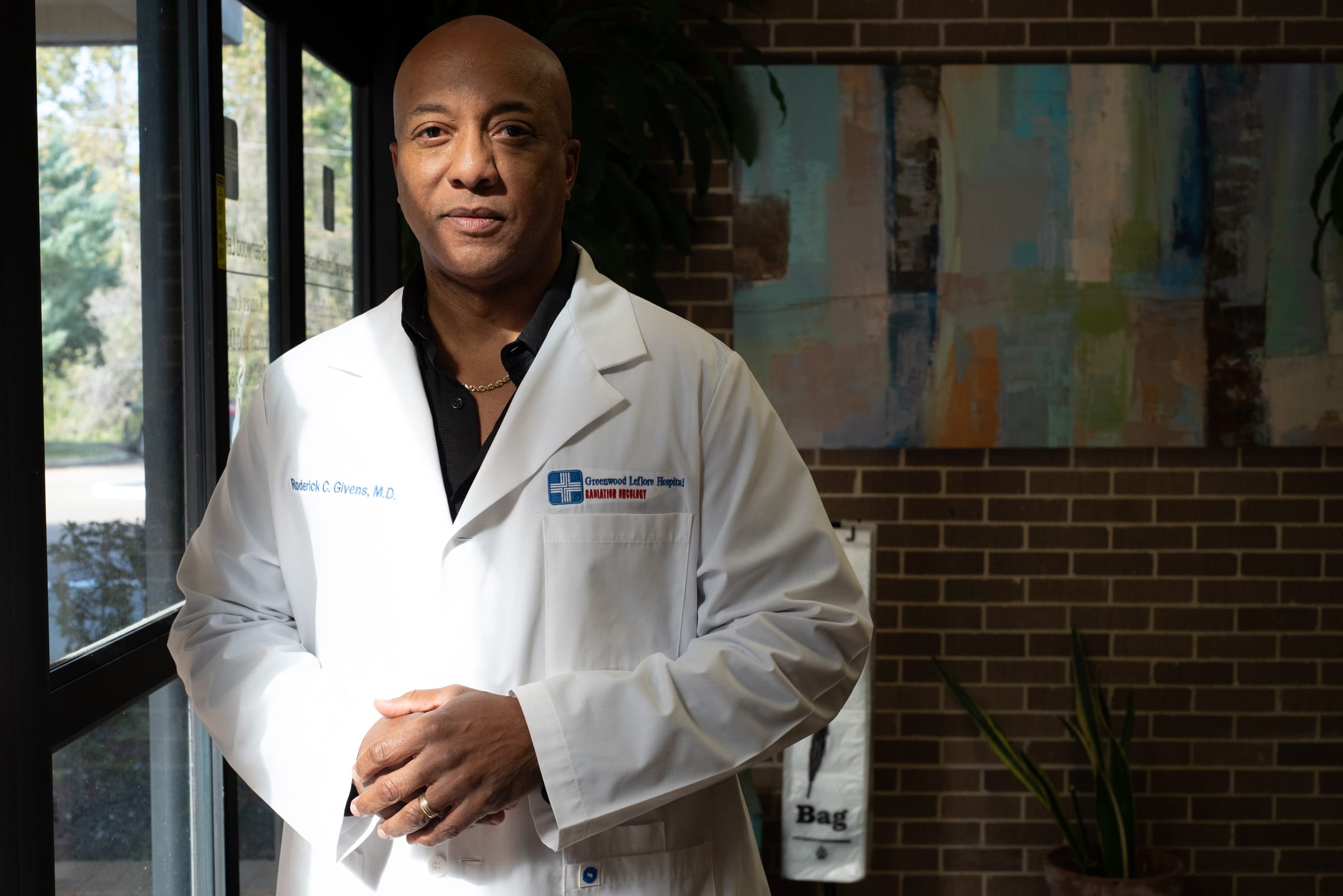

Some locals have already begun looking for new doctors, but Dr. Roderick Givens, a radiation oncologist who has worked at Greenwood Leflore for 15 years, says it can be difficult for patients to make even local appointments.

After Humphreys County Memorial Hospital closed in 2013, some residents in Humphreys County, which borders Leflore County, now had to travel further for health care than they did a decade earlier.

Residents will have to go to North Sunflower Medical Center in Ruleville, approximately 31 miles distant, or South Sunflower County Hospital in Indianola, about 28 miles away, for an emergency room if Greenwood Leflore shuts.

“It essentially equates to a death sentence,” Givens said. “A hospital 10 minutes away now becomes half an hour away.”

The prospect of the hospital closing has made Sibley consider leaving the Mississippi Delta town she’s called home since she was a child.

“If something happens with them, it happens with me,” she said of the hospital.

Making such arrangements, however, necessitates the availability of resources such as cash and automobiles. Poverty affects over 30% of Greenwood people and 25% of Leflore County citizens. According to census data, about 13% of people live in houses without an automobile.

Since Greenwood Leflore’s labour and delivery unit closed, many pregnant residents have had to travel 45 minutes to a University of Mississippi Medical Center satellite hospital in neighbouring Grenada County to give birth. Greenwood’s only option is the hospital’s emergency room.

In this community, lower life expectancy rates have already meant that residents bury their loved ones earlier in life than those born in more prosperous areas.

Residents here understand that a full tank of gas and reliable transportation will not always be enough to overcome the disparities that are at the root of the state’s maternal and infant health crisis.

Mississippi has the highest infant mortality rate in the country, and pregnancy-related deaths are more common than the national average. Black women in the state are nearly three times more likely than white women to die while pregnant, within a year of giving birth, or at the end of their pregnancy.

Pregnant women and newborns are especially vulnerable in the Delta, where some counties lack OB-GYNs.

Kayla Wheeler had several close calls during her pregnancy before giving birth to a healthy baby girl last year at Greenwood Leflore.

The 24-year-old suffers from epilepsy. She had a seizure in a shoe store shortly after learning she was pregnant and was taken to the hospital.

She was taken again at 30 weeks pregnant. Wheeler had just arrived at her sister’s house and was getting ready to leave for a day trip to Jackson when she noticed she was bleeding on the ground.

Wheeler had already decided on a name for her baby girl. She was now concerned that her baby would not survive.

“I thought I was going to lose her,” she said.

Wheeler and her baby were fine, thanks to her sister’s fiancé’s quick arrival at Greenwood Leflore.

“It’s good I got to the emergency room in time. Otherwise, things could have went left,” Wheeler said.

When Greenwood Leflore first opened its doors in 1906, it was housed in a mansion that had been converted into a medical facility.

By the time Jordan, the son of a sharecropper and now a state senator, enrolled at Mississippi Valley State University, a historically Black university in the Mississippi Delta, in 1955, the hospital had relocated to its third location, a short distance from the town’s main street, where it still stands today.

Jordan recalls being quarantined there for a short time in 1964 after he and his wife, a nurse, tested positive for tuberculosis and were transferred to a sanatorium to recover.

Jordan, who has represented Greenwood for nearly three decades, now says that when he goes to the store, he is frequently approached by residents who are concerned about the hospital’s future.

“People up here are in tears almost,” he said.

Jordan said that the hospital’s financial situation has deteriorated as Mississippi remains one of 11 states that have not implemented Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act. Economists anticipate that the first year of expanded Medicaid eligibility will deliver $1.6 billion in federal cash to the poorest state in the country.

“It’s just been an injustice to the poor, rejected and downtrodden,” Jordan said.

The former schoolteacher is disappointed that politicians have not intervened to alleviate the hospital’s problems. The state Legislature, which regularly convenes in January, was called back to the Mississippi Capitol this month for a special session to approve roughly $247 million in tax breaks for a private aluminum mill firm.

Jordan voted in favor of the project, which is expected to bring 1,000 high-paying jobs to an already thriving region of the state, but questions why potential economic deals are met with urgency, “but when our hospitals are closing, nobody wants to come to our rescue.”

“I’m looking at the unfairness of the process,” Jordan said.

Republican Gov. Tate Reeves did not immediately reply to a request for comment.

According to Mississippi Today, a nonprofit newspaper, Marchand, the interim CEO, wants lawmakers find a way to enhance Medicaid payments to hospitals, an intervention that is also among the Mississippi Hospital Association’s legislative goals.

Marchand did not elaborate, but stated that the concept is distinct from the Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act that Reeves rejected.

Meanwhile, many Delta residents are concerned that one of the state’s most disadvantaged communities is losing access to health care. This summer, the region’s final newborn critical care centre shuttered in neighboring Washington County.

Kayla’s mother, Serita Wheeler, had had enough. She sees no future for her children and grandkids in Leflore County if the hospital closes. If Greenwood Leflore goes bankrupt, she may go to Maryland, where she has family.

“I know if I move to Baltimore, Johns Hopkins isn’t closing,” she said.