An international team of scientists has discovered a gene mutation linked to an early onset of Alzheimer’s disease. The scientists tracked the DNLA flaw from several members of a single family.

Alzheimer’s has been wiping out memories and destroying a person’s sense of self for years already. Most cases begin after the age of 65 and symptoms start to show occasionally, but eventually, lead to being an incurable brain disease.

Just recently, the team of scientists lead by neurobiologists in Sweden found an exceptionally rare form of the disease found in one family. This form of Alzheimer’s is found to be quick and steals its victims’ productive years and cognitive functions. This discovery is named the Uppsula APP deletion, from the family that was given this rare Alzheimer’s form. This disease causes a person to have dementia at a young age, Medical Express reported.

“Affected individuals have an age at symptom onset in their early forties, and suffer from a rapidly progressing disease course,” said Dr. Maria Pagnon de la Vega in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

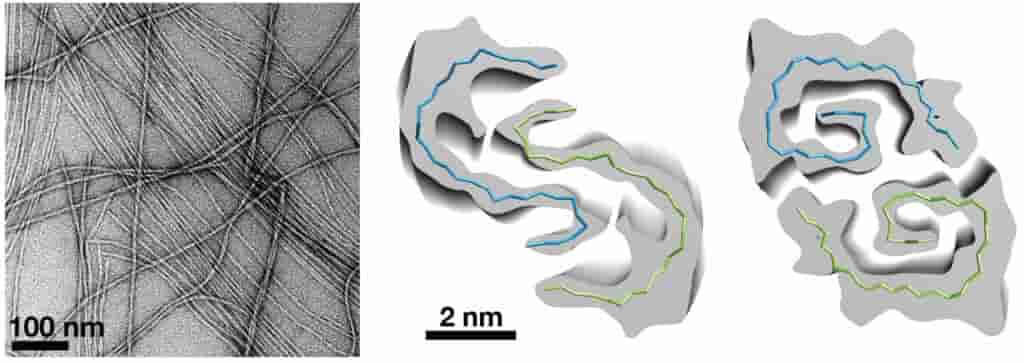

The researchers used multiple state-of-the-art tools to discover the flaw that showed prominently in one family. They found that the mutation accelerates the creation of brain-damaging protein plaques, also known as amyloid-beta, or AB. These plaques destroy neurons and cause the brain to destroy its executive functions.

The executive functions are defined as working memory, mental flexibility, and self-control. There are other forms of Alzheimer’s that have been associated with mutations in the APP gene but this specific one is a deletion that pagnon de la Vega and colleagues were able to confirm through genetic analysis, structural biological research, studies of amino acid and protein chemistry, and mass spectrometry to illustrate the amyloid, or the deleterious protein, that infuses the brain tissue of mutation carriers.

In the mutation carriers, all had a deletion in a specific string of amino acids which are part of the amyloid precursor protein, and in this, the amino acids are missing.

The amino acid ‘beads’ are missing in the strand because the APP gene in the family doesn’t code for them. The deletion cuts out a strip of six amino acids, which results in destructive deposits of AB protein that affects the entire brain.

The story of the family to which the rare form was discovered started seven years ago in Sweden when two siblings went to a memory disorder clinic at Uppsala University Hospital. They were assessed for problems with memory, losing a sense of direction, and the feeling that mental sharpness is leaving them. At that time, the siblings were 40 and 43 and they were not the only ones who were experiencing the confusing symptoms, another relative to their age has similar symptoms.

Another member of the family, a cousin of the siblings, went to the same clinic for evaluation of cognitive concerns that were stealing memory, annihilating out the ability to speak clearly with thoughtful phrases, and destroying the ability to perform simple math. All three members of the family were diagnosed with early onset Alzheimer’s disease. But, other members were having the same issues.

Two decades earlier, physicians treated the father of the two siblings. The same with the three members of the family that came for examination, the father was also in his early 40’s when symptoms showed up. The father was evaluated at the same clinic where his two children became patients as well.

Researchers define this form of Alzheimer’s disease as autosomal dominant, which is passed from one generation to the next, and moves quickly. No data suggest that other members have the same Uppsala APP deletion, but other forms of familial Alzheimer’s were identified in Sweden.

There were already 50 APP gene mutations discovered worldwide before finding out about the deletion. APP mutations are generally responsible for less than 10% of early onset cases. The rare Uppsala APP deletion is the first multiple amino acid deletion that advances to early onset Alzheimer’s.

At present, there is no cure for this disorder and it is expected to devastate the global health care systems come 2050 because of the inevitable aging population, according to the World Health Organization.